|

Bluegrass Vocals

By Fred Bartenstein (unpublished paper, 4/27/10) All rights reserved. Not to be quoted without attribution or published without permission.

There has been a lot more written about bluegrass instrumental techniques than there has about vocals. That seems odd, because bluegrass performances and recordings almost always feature the human voice. A few concepts will help you to better understand and appreciate bluegrass singing. This short article will cover solo vocal styles, commonly used bluegrass harmonies, and suggested resources for listening.

History and Overview

Bill Monroe was the first bluegrass singer, but bluegrass wasn’t the first music he sang. Like many youngsters in the rural South, Monroe attended singing schools led by traveling music teachers. There he learned a simplified “shape-note” system of musical notation that had evolved from the one used in The Sacred Harp (1844), one of several early shape-note hymnbooks spawned by the Second Great Awakening and published during the 19th century. When you hear people singing “fa-so-la-mi” syllables the first time through a gospel number, you’ll know you’re listening to shape-note singing.

Monroe also heard unaccompanied ballads, some of them tracing to the British Isles and the Elizabethan era. Before people had newspapers, radio, or TV, they conveyed news and tragic or touching events through song. Parents commonly used ballads and hymns to quiet, amuse, or teach their young children – and to help pass the time while engaged in their work.

A third influence upon Bill Monroe and the rest of his generation was the music of the day, home-delivered through the new technologies of phonograph and radio. For the first time in history, rural dwellers could readily be exposed to the techniques of white and black performers in a variety of styles: folk and original music; popular ditties from Tin Pan Alley, minstrel shows and vaudeville; and, at least indirectly, the operatic sounds of singers like Jenny Lind or Enrico Caruso.

All these influences found their way into the ears and out of the mouths of Bill Monroe and his contemporaries, as they created bluegrass singing techniques through the methods of trial and error, mix and match.

Largely because Bill Monroe self-trained his adult voice into a tenor range, bluegrass songs are pitched in higher keys than those used in other genres – such as folk, country, cowboy, pop, blues, or gospel – where the same song material is likely to be found. Whatever their gender or vocal part, bluegrass singers are likely to be vocalizing at the upper reaches of their range. This stylistic technique contributes to the intense and strident sound for which bluegrass is known (musicians like to call it an “edge”). One other explanation for the “high lonesome sound” may be found in Sacred Harp singing, where the highest-pitched male vocalists typically sing the melody line.

Bluegrass singers hardly ever use vibrato (a slight and rapid variation in pitch) for coloration. Instead, they tend to value soulful vocal “turns” or ornamentations (short melodic figures used to vary a long-held note, as in “Ah-I am a ma-an of constant sorrow-ow-ow-ow”).

As generations of artists have proven, virtually any song can be performed in bluegrass style. Part of what makes the arrangement “bluegrass” is the rhythmic setting that is used – the particular tempos and syncopations. Bluegrass songs are also distinguished by characteristic methods of solo and harmony singing, and by particular types of vocal arrangements.

Solo Singing Styles

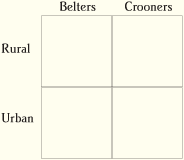

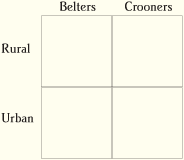

Bluegrass vocal styles can be categorized into four essential types. Two of the dimensions – “belting” and “crooning” – relate to the forcefulness of sound production. The other two – “rural” and “urban” – characterize the way of pronouncing song words. Most bluegrass singers can easily be classified within one quadrant of the resulting matrix:

Belting (Production)

Belting singing styles arose prior to the invention of microphones. In order to be heard across long distances and over loud instruments, singers had to produce loud and forceful tones. Before telephones, elaborate “hollers” and yodels helped neighbors to stay in touch; these also influenced belting singing styles – including that of Bill Monroe who, recalling men hollering as they walked along the nearby railroad tracks, sought to include that sound in his music. Stylistically, belters employ their vocal power to rivet listeners’ attention to the lyrics.

Crooning (Production)

Microphones and sound amplification technology were invented beginning in the 1870s and to this day continue to be refined and improved. Access to the new equipment facilitated changes in instrumentation. String basses replaced tubas at the low end, and electric guitars replaced tenor banjos at the high end. Likewise, singers rejoiced that their words could finally be understood, at a whisper or a roar, without having to yell. The new technique, which came to be known as “crooning,” was first associated with Bing Crosby in the 1930s, the very era when the early ingredients of bluegrass were being assembled. Crooners use the microphone, subtle shadings, and ornamentation to add emotional depth to their singing.

Rural (Inflection)

People growing up in isolated areas develop distinctive ways of speaking and of singing. The people who made early bluegrass sang just as they spoke – for example, pronouncing the lyrics “on and on I follow my darling” as “own an’ own ah fallah mah darlin’.” In the modern era, few children escape the constant barrage of “standard” speakers on radio and TV, or the influence of well-meaning teachers trying to prepare youngsters for careers other than bluegrass singer. Today’s young vocalist with a rural inflection is probably from the South or a Southern migrant family, and/or attends a church where services are conducted entirely in rural speech patterns. Rural-type singers tend to be influenced by the sounds of classic country and gospel music.

Urban (Inflection)

By “urban,” I really mean “not from the rural South.” Most modern American singers lack a distinct geographic accent. (In the ‘60s and ‘70s, Joe Val and Herb Applin brought their broad New Englandese to bluegrass standards such as “Hod-Hotted Hotbreaker,” “Come Wok With Me,” and “You’ll be Re-wadded Over There”). Urban-type singers tend to reflect influences of rock ‘n roll, rhythm and blues, pop, and jazz music. Singers with international accents are becoming more common in the worldwide bluegrass scene, and I would include them in this category as well.

Here are examples of well-known bluegrass singers who fall within the four classifications:

Rural Belters

Hazel Dickens

James King

Del McCoury

Bobby Osborne

Rhonda Vincent

Rural Crooners

Evelyn and Suzanne Cox (Cox Family)

Lester Flatt

Lynn Morris

Jesse McReynolds

Doc Watson

Urban Belters

John Cowan (New Grass Revival, John Cowan Band)

John Duffey (Country Gentlemen, Seldom Scene)

Peter Rowan

Dan Tyminski (Alison Krauss and Union Station)

Joe Val

Urban Crooners

Chris Hillman

Alison Krauss

Claire Lynch

Tim O’Brien

Tony Rice

Issues of Singing Styles

Whether you are a listener or a singer (or both), consider and listen for the following issues connected with the various singing styles:

1) Crooners have trouble being heard in jam sessions or when the power goes off.

2) Belters dueting with crooners need to be much farther from the microphone in order to blend well.

3) People who grow up in urban speech communities tend to sound affected when they try to sing with a rural inflection.

4) Rural and urban singers have trouble blending their words. One or the other needs to adapt, to avoid a clash of different vowel or consonant sounds.

5) Bluegrass singers for whom English is not a native tongue face particular issues: pronouncing English lyrics understandably, and/or conveying the essence of bluegrass vocal style in a different language.

Duets

If one vocal part sounds good, two can sound even better. This line of reasoning led to styles of harmonizing that wound up in bluegrass. The most obvious is the brother-duet sound that first arose in the early ‘30s, displacing rural string bands among country music record buyers and radio listeners.

Brother duets were efficient musical organizations. The two members, most but not all related by blood, typically played mandolin and guitar or two guitars, and sang songs entirely in harmony or in solo verses and harmony choruses. Invariably the lower-voiced singer took the melody (“lead”) line and the higher-voiced singer a harmony line pitched above the melody (“tenor”). Note that this arrangement is the opposite of conventional European/American vocal music such as mainstream church hymns, where the melody is normally restricted to a top voice or soprano line sung by females. Using the word “lead” to refer to a hymn’s melody is an old shape-note singing tradition from eastern Tennessee.

Brother duets were the rage during the era in which bluegrass first arose. Most of the first-generation bluegrass singers began in a brother duet, and all were exposed to a rich repertoire of songs performed by acts such as the Delmore Brothers (Alton and Rabon), the Blue Sky Boys (Bill and Earl Bolick), Mainer’s Mountaineers (Wade Mainer and Zeke Morris), and the Monroe Brothers (Charlie and Bill). Those brother duet styles survive intact within the fuller instrumental context of bluegrass.

Several later brother-duet acts – contemporary with bluegrass – also contributed many songs to the bluegrass canon. These included the Louvin Brothers (Charlie and Ira), Johnnie (Wright) and Jack (Anglin), as well as the duet of Roy Acuff and Oswald Kirby.

Because duets incorporate only one harmony line, the tenor singer has great freedom to choose harmonizing notes that are close (the third or the fourth above the lead) or more widely separated (the fifth, sixth, or seventh above). An affecting duet technique – occasionally heard in bluegrass – where a rising line ends on a unison note then descends in harmony was practiced by The Carter Family (as in “Little Joe”) and Monroe Brothers (as in “Where is My Sailor Boy?”). This technique is helpful when the two singers have similar ranges and the tenor simply can’t reach a harmony above the top note of the melody.

The highest-voiced tenor singers (Bill Monroe, Curly Seckler, Ira Louvin, John Duffey, Hazel Dickens, Joe Val) were especially able to choose dramatic intervals to decorate their duets. Bill Monroe and Jimmy Martin’s experimentation with unique bluesy harmonies – where neither part selects the expected note (as in “Memories of You” or “I’m Blue, I’m Lonesome”) – has never been equaled or advanced since their stunning recordings of the early ‘50s.

The listener and aspiring singer can choose from a wealth of wonderful recorded duets. Here are some that should not be missed:

Bill Monroe and Lester Flatt (Blue Grass Boys, mid ‘40s)

Carter and Ralph Stanley (Stanley Brothers, late ‘40s through the mid ‘60s)

Lester Flatt and Curly Seckler (Flatt & Scruggs, late ‘40s through the early ‘70s)

Everett and Bea Lilly (Lilly Brothers, late ‘40s through the mid ‘70s)

Bill Monroe and Jimmy Martin (Blue Grass Boys, early ‘50s)

Don Reno and Red Smiley (early ‘50s through the early ‘70s)

Jim and Jesse McReynolds (early ‘50s through the late ‘90s)

Red Allen and Frank Wakefield (early ‘60s)

Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard (mid ‘60s through the mid ‘70s)

Joe Val and Herb Applin (early ‘70s)

Tony Rice and Ricky Skaggs (mid ‘70s through the early 80s)

Alan O’Bryant and Pat Enright (Nashville Bluegrass Band, mid ‘80s to the present)

Tim and Mollie O’Brien (late ‘80s to the present)

Wayne Taylor and Shawn Lane (Blue Highway, mid ‘90s to the present)

Alison Krauss and Dan Tyminski (Union Station, mid ‘90s to the present)

Laurie Lewis and Tom Rozum (‘mid ‘90s to the present)

Ricky Skaggs and Paul Brewster (Kentucky Thunder, mid ‘90s to the present).

Ninety-nine percent of all bluegrass duets are arranged in the lead-low/tenor-high style described above. Every rule has exceptions, and two are found in material bluegrass borrows from country music. The Louvin Brothers’ stunning duets sometimes – in the middle of a line – pass the melody from one singer to the other, or pass the harmony from a note above the melody to one below the melody. Singers can’t duplicate certain Louvin songs without decoding and learning these complicated arrangements (sorry music readers, bluegrass sheet music is a virtually unknown commodity). The second exception is a style often heard in country male/female duets (such as Dolly Parton and Porter Wagoner) where the female sings the melody and the male a tenor harmony in the lower octave. While on the subject of exceptions, here’s an interesting footnote: according to brother Sonny, the extremely high-voiced Bobby Osborne tenored their sister Louise on “New Freedom Bell in 1951;” Vern Williams sang above Rose Maddox in the choruses from her 1970s recordings.

Here’s one more style to listen for, mostly in duets and quartets. “Call and response” singing traces to African and other folk-singing traditions. The lead voice sings a solo phrase and the harmony voice(s) immediately follow(s) with the same phrase, or one that extends it or responds. Examples are “There’s a bluebird singing/There’s a bluebird singing” in “Bluebirds are Singing for Me” or “Every day I’m camping/camping, in the land of Canaan/Canaan” in “Camping in Canaan’s Land.”

Trios

Early bluegrass and the old-time southern-mountain vocal styles that preceded it were characterized by solos and duets. Trio singing was most often heard in “Tin Pan Alley” popular tunes, cowboy songs, and European music. In the 1940s, Bill Monroe began experimenting with occasional three-voice choruses. Flatt & Scruggs continued those experiments. On March 1, 1949, the Stanley Brothers and Pee Wee Lambert recorded three stunning trios (“A Vision of Mother,” “The White Dove,” and “The Angels Are Singing in Heaven Tonight”) that established that sound as a permanent part of bluegrass. (The third part of a bluegrass trio that is added to the lead and tenor lines is called the “baritone” line.)

In the years since, most bluegrass acts have included trios in their stage shows and recordings. Trios add variety to those performances, and showcase the wealth of vocal talent in a band. Compared to the large number of famous duets, a relatively small number of trios have established legendary status. Those include the trios of:

Carter and Ralph Stanley and Pee Wee Lambert (Stanley Brothers, ‘40s and early ‘50s)

Jimmy Martin, Paul Williams, and J.D. Crowe (Sunny Mountain Boys, late ‘50s and early ‘60s)

Bob and Sonny Osborne and a succession of singing guitarists (Osborne Brothers, late ‘50s on)

John Duffey, Charlie Waller, and Eddie Adcock (Country Gentlemen, late ‘50s to late ‘60s)

Other trios to include in your “must-listen” agenda are:

Jim and Jesse McReynolds with Don McHan (late ‘50s to the late ‘60s)

Several later versions of the Country Gentlemen (‘70s)

Seldom Scene (early ‘70s on)

J.D. Crowe and the New South (early ‘70s on)

Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver (late ‘70s on)

Hot Rize (‘80s and early ‘90s)

Various combinations of Chris Hillman, Herb Pedersen, and Bill Bryson (e.g. Desert Rose Band, Laurel Canyon Ramblers, ‘80s on)

Longview (‘90s)

IIIrd Tyme Out (‘90s on)

Cox Family (‘90s on)

Rhonda Vincent and the Rage (‘90s on)

Lonesome River Band (‘90s on)

The Isaacs (‘90s on)

Blue Highway (late ‘90s on)

The Chapmans (late ‘90s on)

The Grascals (2004 on)

Starting in the mid-‘70s, bluegrass trios began to eclipse duets. That trend appears to be reversing with the millennium, however. Modern bands are rediscovering lost styles and the comparatively greater freedom of the duet for creative arrangements.

Because the majority of chords used in bluegrass are based on three notes, a vocal trio with each member singing a different note of the chord is the simplest way to create a full and pleasing harmony. Conversely, part doubling – i.e., two members singing the same note, even in different octaves – can result in trio harmony that sounds empty and undesirable. Tones outside the song’s chordal structure are sometimes used within a harmony part’s line, but usually resolve quickly into a consonant chord.

“Stacking” describes how the three parts are voiced in the arrangement of a vocal trio. A standard bluegrass trio places the melody in the middle, with a tenor line above and a baritone line below. A “high baritone” trio places the melody at the bottom, a tenor line above it, and a line sung an octave higher than the standard baritone above that. A “high lead” trio places the melody at the top, a standard baritone line below it, and an octave-low tenor part below that. Here’s a diagram that may help to clarify the trio stacks:

| |

Standard Trio |

High Baritone Trio |

High Lead Trio |

| Highest |

Tenor |

High Baritone |

Lead (Melody) |

| Middle |

Lead (Melody) |

Tenor |

Baritone |

| Lowest |

Baritone |

Lead (Melody) |

Low Tenor |

Vocal groups choose a stack by assessing the ranges of their singers. If the lead (melody) singer has a particularly low voice, they might want or need to go to a high-baritone trio for that song. If the lead is a female or a strikingly high-voiced male and the harmony singers are male, the high-lead trio is indicated. Because the “edge” in bluegrass vocals comes from singing near the top of the singers’ranges, mixed-gender trios with two men tend to be high-lead or high-baritone (such as Alison Krauss’s and Rhonda Vincent’s); with two women, a standard trio sounds best with a high-voiced male baritone (such as the Whites and the Isaacs). Using different stacks is also a way for groups to create more variety in their performances and/or recordings.

As you might guess, there are exceptions and creative variations to the three vocal stacks described above.

1) Sometimes parts cross – most commonly the baritone – to fill harmonic holes between a particularly athletic lead or tenor line.

2) The pedal steel guitar creates its unique voicing effects by raising or lowering one or two notes of a chord while holding the other(s) constant. That instrument came along in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, and inspired contemporary vocal arrangements by the Osborne Brothers and the Country Gentlemen (including some spectacularly ornamented song endings).

3) Cowboy trios often call for three singers to start a line in unison and break into harmony after a few words. That style is occasionally heard in bluegrass.

Another arrangement to listen for is a vocal phrase that starts as a solo, becomes a duet, and ends as a trio ( “Like a fox, like a fox, like a fox” in “Fox on the Run,” “And the walls, and the walls, and the walls...came tumblin’ down” in “Joshua,” or “Get down, get down, get down” in “Get Down on Your Knees and Pray”). In jazz parlance, this technique is called a “pyramid.”

Three singers are not always better than one or two. If you are starting out in a bluegrass band or in jam sessions, resist the tendency to make every song a trio. Ask yourself whether the third voice adds a pleasing dimension to the sound or whether it just crowds the tenor into a less-interesting choice of harmony notes. Also, take the time to make sure that each singer is singing a different note from the others at all times. Part doubling (even in different octaves) sounds “clunky” in a trio. That problem can usually be solved by having the baritone singer cross over the lead, or by adjusting a few notes that the lead or tenor might sing differently in a duet. If you can’t fix the harmony after a few tries, or without lots of part-switching, accept that the song wasn’t meant to be a trio.

Quartets

Think about the word “quartet” and two adjectives jump to mind – barbershop and gospel. Barbershop repertoires and harmonies had little influence in the development of bluegrass music. On the other hand, a huge amount of religious material from both white and black singing traditions lives on in bluegrass gospel quartets. (Unlike barbershop, there are very few secular quartets in bluegrass.)

Choral music in the Western world, going back to the 17th century, has almost always been harmonized in four vocal parts. Singing styles pioneered by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, an African-American college choral group that toured the US and Europe beginning in 1871, inspired “jubilee quartets” in hundreds of black communities. In the early 20th century, itinerant singing schools using the simplified shape-note method of music instruction evolved into a publishing industry. Companies like J.D. Vaughan and Stamps-Baxter commissioned new religious songs and promoted their songbooks with male quartets that toured widely in the South.

Early bluegrass performers were steeped in gospel-quartet sounds. They found that the material sounded terrific with the instrumentation, syncopated rhythms, and singing styles they were using for their secular music. The many inexpensive gospel songbooks provided an easy way to learn new material and expand their repertoire. Gospel quartets were a way for the band to add variety to their performances, share their religious witness, reassure audiences that bluegrass was morally upright, and involve their lowest-voiced singer in the vocals.

From the very beginning, some bluegrass groups – like Carl Story or the Lewis Family – played gospel exclusively, toured in churches, and participated in quartet sings. But most bluegrass bands performed both secular and sacred material (on the Flatt & Scruggs television show, if a commercial ended and the band had their hats off, viewers knew it was time for a gospel number). In fact, it became a bluegrass convention to refer to the quartet separately – kind of a band within a band. On live performances, radio, and TV shows, you’d hear the MC say, “now here’s the Blue Grass Quartet (Bill Monroe), Foggy Mountain Quartet (Flatt & Scruggs), Sunny Mountain Quartet (Jimmy Martin), etc. to sing a fine gospel number.”

It was – and still is – common for quartet performances to be accompanied by a stripped-down band of guitar and mandolin or two guitars, with or without a string bass (the classic brother duet instrumentation). In 1971, Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys initiated a cappella (meaning sung without instrumental accompaniment) gospel quartets as a now-common element of the bluegrass repertoire. A cappella quartets evoke the sound of Sacred Harp singing and religious sects which consider instruments too worldly an accompaniment for praising God. They also permit freedom from strict observance of the meter… but notice how the singers must carefully watch a leader to stay together.

Since there are only three notes in most bluegrass chords, the bass vocalist doubles the note of one of the other singers in quartet harmony passages, but in a lower octave. Like a string bass or guitar, the bass singer may have short solos (“Oh brother,” “Now let us,” “Life’s evening sun,” “Oh, baby”) which lead the ensemble into the first chord, or from one chord to the next.

Almost all bluegrass quartets are stacked in the following manner: bass, baritone, lead, and tenor. Exceptions occur when the highest voice – perhaps a female – takes the melody; there the stack would be: bass, low tenor, baritone, lead. Here’s a diagram that may help to clarify the quartet stacks:

| |

Standard Quartet |

High Lead Quartet |

| Highest |

Tenor |

Lead (Melody) |

| Next to Highest |

Lead (Melody) |

Baritone |

| Next to Lowest |

Baritone |

Low Tenor |

| Lowest |

Bass |

Bass |

Here are some great quartets from the history of recorded bluegrass:

Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and Howard Watts (Blue Grass Boys, mid ‘40s)

Carl Story, Claude Boone, Red Rector and various fourth-part singers (Rambling Mountaineers, late ‘40s and ‘50s);

Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Curly Seckler, and Benny Martin or Paul Warren (Flatt & Scruggs, ‘50s)

Carter Stanley, Ralph Stanley, Al Elliott or Bill Napier, and George Shuffler (Stanley Brothers, late ‘50s)

Don Reno, Red Smiley, Mack Magaha, and John Palmer (Reno & Smiley, mid-’50s to the mid-’60s)

Bluegrass Cardinals (‘70s and ‘80s)

Johnson Mountain Boys (‘80s and 90s)

Nashville Bluegrass Band (‘80s on)

Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver (late ‘70s on)

IIIrd Tyme Out (‘90s on)

Other Variations and Observations

Two of the classic bluegrass groups expanded singing beyond quartets: Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys and Jimmy Martin’s Sunny Mountain Boys. Lance LeRoy, closely associated with Lester Flatt for three decades, observed that whenever Lester announced that the band would “gang around” without specifically mentioning the Foggy Mountain Quartet, he was calling for everyone (usually a quintet) to sing. The quintet stack was: bass, baritone, lead, tenor, and high baritone (doubling the baritone part in a higher octave). The highest voice was either Jake Tullock or Curly Seckler, both males. Particularly in their folk-oriented recordings of the ‘60s, Flatt & Scruggs arranged both secular and sacred material as “gang-around” quintets. Jimmy Martin used the same quintet stack, but employed a female at high baritone – notably Penny Jay, Lois Johnson, or Gloria Belle Flickinger – on gospel numbers exclusively.

Over the years, certain conventions have arisen in bluegrass singing. Some of these make sense and others don’t.

1) Banjo players seldom sing lead, and, when they do, they generally play rhythm chords or don’t play at all. That’s because the mental concentration it takes to sequence the various three-finger “rolls” competes with the process of remembering and presenting song words. The late Billy Edwards of the Shenandoah Cut-ups was an astounding exception to this generality.

2) For the first three decades, it was assumed that the guitar player should be the lead singer and the mandolin player the tenor – just because that was how the Monroe Brothers did it. There is a certain symmetry to low/low and high/high in that arrangement, but it has long since ceased to be a “bluegrass rule.” For a counterexample, listen to Mountain Heart’s mandolin player Adam Steffey’s resonant baritone or Kentucky Thunder’s guitar player Paul Brewster’s piercing tenor.

3) Female singers had to be bass or guitar players or strictly vocalists until Laurie Lewis (fiddler), Lynn Morris (banjo player), Alison Krauss (fiddler), Rhonda Vincent (mandolin player), and their contemporaries shattered that convention in the ‘70s and ‘80s.

4) It was long assumed that the key in which a song was first recorded was sacred. That rule saved instrumentalists the trouble of having to transpose their breaks, and denied large parts of the repertoire to singers with lower or higher ranges. Female bandleaders with the power to set their own rules, instrumentalists with more versatile techniques, and John Hartford’s “low tones” put sacred-key myths to permanent rest. (That said, there is undeniably extra excitement in the “short string” instrumental keys of B and C, if the band has a singer who is literally “up to it.”)

The string bass is usually given its own microphone, to keep its booming tones from overpowering the mix. That makes it awkward – but not impossible – for the bass player to be the featured lead vocalist. Ronnie Bowman overcame the problem by playing a bass guitar. Other singing bassists – Hazel Dickens and Allen Mills, for example – learned to lighten their touch and gracefully heft the large instrument in and out of the “front and center” position.

Where Bluegrass Singing May Be Going

In this brief article, I have summarized the historical influences on bluegrass singing styles, categorized types of bluegrass soloists, reviewed the primary arrangements used in bluegrass harmonies and a few of their variations, and suggested enough recorded music to keep the avid listener busy for the better part of a year. Let us close with a few speculations on how bluegrass singing is likely to develop in the future.

1) The world continues to be less agrarian, less rural, and less isolated. Since those were the conditions under which bluegrass singing styles arose, it is unlikely that they would arise again in today’s circumstances. We are fortunate to already have a wealth of bluegrass vocal styles to draw upon. And we now have the technology and the time to conserve, study, and emulate the best of what has come before.

2) Bluegrass singing was influenced by other styles of music in the past, and it is likely that cross-fertilization will continue. Just as bluegrass was influenced by other forms, it now is a significant force in shaping country, rock, folk, and gospel sounds.

3) Rural and belting singing styles evolved for cultural and technological reasons that are less likely to be duplicated in the future. One can expect urban and crooning styles to become even more prominent in the future.

4) Continuing inclusion of women will be a force for broadening the variety of arrangements and keys used in bluegrass. Similarly, the widening international interest in bluegrass will break the monopoly English has held on bluegrass song lyrics.

5) Musical creativity will push the edges of bluegrass vocals, as it already has instrumental techniques. Future singers and vocal arrangers will rediscover and advance upon the artistic peaks in bluegrass singing established by Bill Monroe and Jimmy Martin in duet singing, by Bob and Sonny Osborne and Red Allen in trio singing, and by Flatt & Scruggs in quartet and quintet singing.

6) Teaching and learning techniques will advance for bluegrass singing, as they have advanced incredibly for instrumentalists since the 1970s. It is noteworthy that Bill Monroe and his contemporaries received formal instruction in singing. The shape-note system by which they learned was analogous to tablature now in common use for teaching string instrument players – both are simplified alternatives to standard musical notation. Bluegrass singing will advance when more bluegrass songs (particularly harmony arrangements) are annotated, and when more vocalists learn to read music – either in standard notation or a simplified system yet to be invented.

7) Audiences will become more sophisticated in their appreciation for bluegrass singing. We have come a long way since 1959, when Earl Scruggs was invited to the Newport Folk Festival without Lester Flatt, because bluegrass banjo was considered more worthy and acceptable than bluegrass singing. Indeed, the commissioning of this very article may someday be seen as a pivotal step in the recognition of bluegrass vocals as an artistic form.

Three Picks from the Rounder Catalog

I’ve been asked to suggest from the vast Rounder catalog the three CDs that best exemplify bluegrass vocal traditions. While that is obviously impossible, here are three you mustn’t miss in your listening adventures:

The Bluegrass Album, Volume One (J.D. Crowe, Tony Rice, Doyle Lawson, Bobby Hicks, Todd Phillips) Rounder CD 0140 (1981)

All of the Bluegrass Album Band projects (except Volume 6, which is all-instrumental) contain wonderful examples of singing styles, performances, and how classic material can be re-arranged to sound fresh to modern ears. Let’s start with the individual singers. Tony Rice is an urban crooner, uniquely able to project facets of Lester Flatt, Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin, and Red Smiley, as well as his own distinctive California/Carolina lead-singing style. Doyle Lawson is one of the smoothest rural belters, with the range to hit the most intense and interesting choices of tenor notes in duets, and the power to nail home a straight or high lead. J.D. Crowe is the essential architect of the bluegrass baritone part, with an uncanny ability to add a strong third note without drawing attention to himself in the blend. Bobby Hicks’ resonant bass notes are a satisfying anchor to the quartets. Volume One offers five Bill Monroe songs (two from the Lester Flatt era and three from the Jimmy Martin era, including a call-and-response quartet), four Flatt & Scruggs standards (including three Lester Flatt/Curly Seckler duets), a Jimmy Martin and the Osborne Brothers trio, and a gospel trio from the repertoire of J.D. Crowe & the Kentucky Mountain Boys.

Back Home Again (Rhonda Vincent) Rounder CD 0460 (2000)

Rhonda Vincent has the strongest voice of the modern female belters; she sings with a subtle rural inflection that doesn’t grate on mainstream tastes. On her debut Rounder album, she combines the power and focus of a Jimmy Martin or Wilma Lee Cooper with the harmonic sophistication of a Louvin or Osborne brother. You’ll get from this album a sterling example of family harmony, as Darrin Vincent belts baritone, low tenor, and lead (in the chorus) parts in the upper tenor range needed to support his sister’s diamond-hard soprano. Back Home Again shows how a high-voiced lead singer like Rhonda can switch to tenor on choruses or top a high-lead trio. If you like puzzles (or tennis), figure out how the melody is deftly passed from the low to the high duet partner on the Ira Louvin-penned “Out of Hand.”

Longview (Dudley Connell, Glen Duncan, James King, Joe Mullins, Don Rigsby, Marshall Wilborn) Rounder CD 0368 (1997)

Maybe it’s cheating to put two “supergroup” special recording projects in my top-three list, but for vocal quality and variety it would be hard to beat Longview. The idea for the group began when James King, Dudley Connell, and Don Rigsby recreated the Stanley Brothers and Pee-Wee Lambert’s haunting 1951 high-baritone trio “The Angels are Singing” in 1994 at a North Carolina festival. That harmony stack and melody were echoed in this album with “Lonesome Old Home,” an even more obscure bluegrass classic that took the International Bluegrass Music Association’s Song of the Year award in 1998. Like a bluegrass mad scientist, album producer Ken Irwin realized that by combining the most soulful rural-belting lead singer to come along in two generations (James King) with three rural-belting tenors (Dudley Connell, Don Rigsby, and Joe Mullins), he could rule the world. The CD is a catalog of the vocal arrangements outlined elsewhere in this article. You’ll hear a pre-bluegrass brother duet, straight duets (with lots of great tenor note choices), solos, a call-and-response gospel duet, and a generous helping of high-baritone trios. There’s even an example of the pyramid technique in “The Touch of God’s Hand.” All the tempos are included, from “pitiful” slow to lightning-fast. And there are songs in seven different keys!

Fred Bartenstein is the son of a Virginia-born brother-duet tenor, and a bluegrass music historian, broadcaster and journalist. The author gratefully acknowledges comments and advice on preliminary drafts of this paper, particularly from Kevin Kehrberg (professional bluegrass musician and doctoral candidate in musicology at the University of Kentucky) and also from Anna Bartenstein, Joanne Brooks, Nancy Cardwell, Wayne Erbsen, Lance LeRoy, and Jon Weisberger.

|