|

Fred Bartenstein has always seemed to find himself perfectly situated to pursue his life-long interest in bluegrass music – as he puts it, “I’ve always seemed to be in the right place at the right time.” This luck has allowed him to find bluegrass in the most surprising places, whether at a private day school in New Jersey, or at Harvard University in the late 1960s. It has also meant that, among other things, he found himself attending the first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Va., becoming a bluegrass DJ at the age of 16, starting Muleskinner News Magazine, and playing rhythm guitar and singing with a long list of pickers from Don Stover and John Hartford to Frank Wakefield and Dorsey Harvey. Fred Bartenstein has always seemed to find himself perfectly situated to pursue his life-long interest in bluegrass music – as he puts it, “I’ve always seemed to be in the right place at the right time.” This luck has allowed him to find bluegrass in the most surprising places, whether at a private day school in New Jersey, or at Harvard University in the late 1960s. It has also meant that, among other things, he found himself attending the first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Va., becoming a bluegrass DJ at the age of 16, starting Muleskinner News Magazine, and playing rhythm guitar and singing with a long list of pickers from Don Stover and John Hartford to Frank Wakefield and Dorsey Harvey.

How It All Started

Born in 1950, Bartenstein started listening to music very young, and has never stopped. Fred grew up with a rich musical background. His father and an uncle had a guitar-mandolin duo on Wildcat Mountain in Northern Virginia. As Fred puts it, “My father understood and appreciated the music and my maternal grandmother genuinely liked it.” A cousin from Tennessee taught him the songs of the famous Carter Family and other classic country tunes. Fred recalls that his love for traditional music was expressed early. “When asked in first grade, during a visit to radio station WREL in Lexington, Va., what kind of music I liked, I immediately replied ‘mountain music!’”

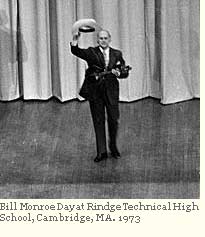

Fred remembers listening every morning to Red Smiley and the Bluegrass Cut-Ups on WDBJ-TV in Roanoke, Va. “Red Smiley was my hero.” Perhaps most crucial in Fred’s musical education was attending a pathbreaking 1964 concert in New York City’s Madison Square Garden. “It had the whole cast of the Grand Ole Opry, everyone from the Wheeling Jamboree, Texas musicians, California musicians, Canadian musicians – just about everyone seemed to be there, each playing one or two songs. My dad had told me that if there was somebody I really liked, he would buy me the record. When a guitar player came out with his Martin guitar and a great fiddle player – which turned out to be Hank Snow and the Rainbow Ranch Boys, with Chubby Wise – I though I had my guy. But then a little later, a gentleman came out carrying what looked like a ukulele, hit a couple of quick notes, and started singing ‘Good Morning, Captain.’ I turned to my Dad and said ‘That’s it!’ That’s how I was introduced to Bill Monroe.” Fred remembers nostalgically that he could go to the local drugstore back then and find those records – Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, the Carter Family, the Stanley Brothers.

Bartenstein himself seems somewhat surprised at the fact that at Pingry School, a private high school in Elizabeth, N.J., one could find two bluegrass bands. When Fred graduated in 1968, “It was the only time a private school in New Jersey could claim to have a bluegrass scene.  There wasn’t one there before, and there hasn’t been one since.” During those years, Fred came to learn of the many players in and around New York City. There wasn’t one there before, and there hasn’t been one since.” During those years, Fred came to learn of the many players in and around New York City.

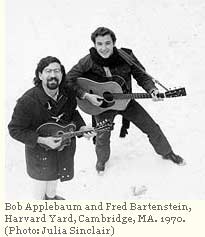

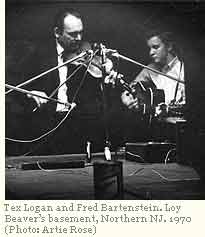

He talked and played with many of the musicians one could hear in Washington Square: Pete Wernick, David Grisman, Bob Applebaum, David Bromberg, Kenny Kosek, Winnie Winston, Tex Logan, and others. Graduating from high school, Fred found himself living and working in a public housing project in Newark, N.J., driving at night to New York’s famous Gerde’s Folk City to play with the Greenbriar Boys, which included Frank Wakefield and Joe Isaacs. It was during this time that, under the name “Joe Isaacs and the Lonesome Drifters,” Wakefield and Isaacs, along with Bartenstein, Richard Greene, and Kevin Smythe, recorded an album that wasn’t released until 1981.

Bluegrass in the Strangest Places

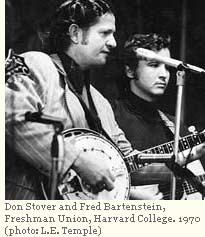

Less surprising was Fred’s decision to attend Harvard University. “My decision on where to go to college was based entirely on bluegrass. My most compelling reason to go to Harvard was that Boston had a thriving bluegrass scene, and none of my other choices could say that. At that time, the Lilly Brothers had been playing at Boston’s Hillbilly Ranch for some 20 years. Playing around town were Bill Keith, Peter Rowan, the Charles River Valley Boys, Joe Val, and many others. It was a strange time to be doing bluegrass, but then, as now, it was my community. It was a college subculture and compared to the drug scene, it was a healthier, smarter, and generally a much better alternative.” Less surprising was Fred’s decision to attend Harvard University. “My decision on where to go to college was based entirely on bluegrass. My most compelling reason to go to Harvard was that Boston had a thriving bluegrass scene, and none of my other choices could say that. At that time, the Lilly Brothers had been playing at Boston’s Hillbilly Ranch for some 20 years. Playing around town were Bill Keith, Peter Rowan, the Charles River Valley Boys, Joe Val, and many others. It was a strange time to be doing bluegrass, but then, as now, it was my community. It was a college subculture and compared to the drug scene, it was a healthier, smarter, and generally a much better alternative.”

Again finding himself in the right place to be playing bluegrass, Fred sat in with the Lilly Brothers on Bea Lilly’s night off, as well as playing with Don Stover’s White Oak Mountain Boys. He also played a good deal with Richie Brown, a dentist in Cambridge, Mass. Brown was “a good mandolin player, and the only African American Bluegrass musician I’ve ever played with or known.”

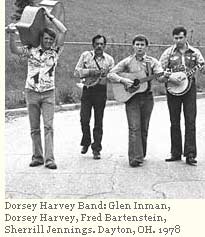

The Bluegrass Scene in Southwest Ohio

Fred moved to Dayton, Ohio, in 1975, explaining “I needed to be in a good bluegrass scene.” He found it in Dayton, which at the time had a wide variety of excellent pickers in and around the area. After playing in bars with Jack Lynch, Fred joined John Hartford to play a cruise on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on the Delta Queen, along with Katie Laur and Doug Dillard. He then played some seven years with Dorsey Harvey. “We were a good local bluegrass band in a good bluegrass market, playing nightclubs, country clubs, and everywhere in between around Dayton, sometimes venturing down to Cincinnati.” Fred moved to Dayton, Ohio, in 1975, explaining “I needed to be in a good bluegrass scene.” He found it in Dayton, which at the time had a wide variety of excellent pickers in and around the area. After playing in bars with Jack Lynch, Fred joined John Hartford to play a cruise on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on the Delta Queen, along with Katie Laur and Doug Dillard. He then played some seven years with Dorsey Harvey. “We were a good local bluegrass band in a good bluegrass market, playing nightclubs, country clubs, and everywhere in between around Dayton, sometimes venturing down to Cincinnati.”

Bartenstein points to such players as Red Allen, the Allen Brothers, Noah Crase, Paul Mullins, Harley Gabbard, Dave Evans, and Earl Taylor who carried on a rich tradition in southwestern Ohio. When Doug Dillard asked Fred to accompany him on a tour of Europe, Fred realized he had to make a decision. “I could make a living as a musician, but I knew I would never be a great musician. I had a new job in the Dayton City Manager’s office, and I decided bluegrass was not going to be my career.” After Dorsey Harvey’s death in the 1980s, Fred took some time off from playing, but has recently begun playing again, laying down rhythm and vocal tracks with Dayton banjo player Robert Leach and performing at social occasions.

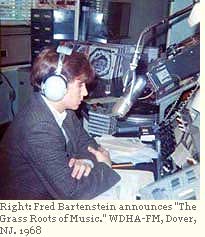

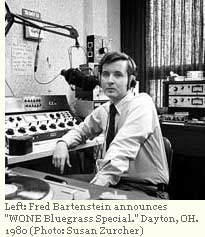

Fred On The Air

Fred likes to point out that in the church choir he’s a tenor, and will usually sing lead in a bluegrass band. One can hear Fred on record singing “Wild Bill Jones” on Vassar Clements’ album “Crossing The Catskills” and singing “I Hope You Have Learned” on Del McCoury’s “Livin’ On The Mountain.” And though he decided against a career as a professional musician, Bartenstein has stayed in close contact with the bluegrass community and has recently returned to a first love – playing music on the radio. Fred likes to point out that in the church choir he’s a tenor, and will usually sing lead in a bluegrass band. One can hear Fred on record singing “Wild Bill Jones” on Vassar Clements’ album “Crossing The Catskills” and singing “I Hope You Have Learned” on Del McCoury’s “Livin’ On The Mountain.” And though he decided against a career as a professional musician, Bartenstein has stayed in close contact with the bluegrass community and has recently returned to a first love – playing music on the radio.

At the age of 16, Fred could be found playing bluegrass on WREL out of Lexington, Va., as well as doing everything else, from spinning rock’n’roll 45s to giving the farm report. In addition to working on WREL, Fred has had a radio show playing country music with [the late] Bill Vernon on WBAI in New York City, a Saturday afternoon folk music show for classical FM station WDHA in Dover, N.J., (which he turned into a pure bluegrass show), and has helped with Hillbilly at Harvard on WHRB.

In the late 70s he had a Sunday night bluegrass show on Dayton’s WONE. From 1985 to 1992, he could be found on a variety of WYSO Yellow Springs, Ohio’s public radio shows, such as "Faded Love," "The Country Music College Of The Air," and "Bluegrass Countdown." Along the way, Fred has accumulated a collection of recordings of bluegrass, country, and old-time music from the 1920s to the present. In the late 70s he had a Sunday night bluegrass show on Dayton’s WONE. From 1985 to 1992, he could be found on a variety of WYSO Yellow Springs, Ohio’s public radio shows, such as "Faded Love," "The Country Music College Of The Air," and "Bluegrass Countdown." Along the way, Fred has accumulated a collection of recordings of bluegrass, country, and old-time music from the 1920s to the present.

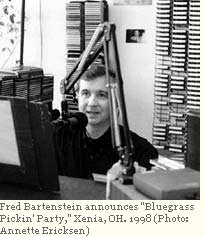

Since November of 1997, Fred has worked for Joe Mullins’ WBZI, doing a Saturday morning bluegrass show. “Nowhere else can I play whatever I want to and only what I want to – which means outstanding bluegrass music for a well-informed audience. Many members of my audience are migrants from Kentucky and Tennessee, and they have excellent taste.” He lists the kinds  of requests his listeners make – Blue Highway, Bobby Hicks, Rob Ickes, Alison Krauss’s “So Long, So Wrong,” Longview, the Del McCoury Band, Ricky Skaggs’s “Bluegrass Rules!,” the “True Life Blues” tribute to Bill Monroe – and explains that it is this kind of music that makes him excited about getting to the microphone each Saturday morning. of requests his listeners make – Blue Highway, Bobby Hicks, Rob Ickes, Alison Krauss’s “So Long, So Wrong,” Longview, the Del McCoury Band, Ricky Skaggs’s “Bluegrass Rules!,” the “True Life Blues” tribute to Bill Monroe – and explains that it is this kind of music that makes him excited about getting to the microphone each Saturday morning.

The Bluegrass Festival

No discussion of Fred’s lifelong involvement with country music in general, and bluegrass music in particular, would be complete without considering his early role in what has become the classic bluegrass event: the festival. “I was working on a survey crew in Lexington in 1965, when I heard on the radio that there was going to be a big bluegrass festival at Cantrell’s Horse Park in Fincastle, Va. Freddie Goodhart, an old friend, drove me down with my Gibson J-50.” The first night Fred remembers sitting around picking with some other musicians when a drunk stumbled up and pulled a gun on him and Goodhart. “He said ‘play “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” and if I don’t like the way you play it, I’ll blow your head off!’ He must have like the way we played it, because he gave us a beer afterward.”

“Bluegrass music had just been kicked out of country music at the time of that first festival. We all felt in ’65 that we were attending an Irish wake for bluegrass – for Monroe, the Stanleys, Jimmy Martin, Don Reno, Red Smiley, and Mac Wiseman.” Fortunately, things turned out much differently.

One moment from the 1966 festival remains especially vivid to this day. “Bill Monroe and the Osborne Brothers were singing ‘I Hear A Sweet Voice Calling,’ and something almost indescribable happened: no one could move, and a complete stillness came over the entire audience, after which Bill and the rest of us broke into tears. It was a transcendent moment that couldn’t be captured on tape, but anyone there will remember it.” Fred recalls a New England couple on their honeymoon letting him sleep in their car. One moment from the 1966 festival remains especially vivid to this day. “Bill Monroe and the Osborne Brothers were singing ‘I Hear A Sweet Voice Calling,’ and something almost indescribable happened: no one could move, and a complete stillness came over the entire audience, after which Bill and the rest of us broke into tears. It was a transcendent moment that couldn’t be captured on tape, but anyone there will remember it.” Fred recalls a New England couple on their honeymoon letting him sleep in their car.

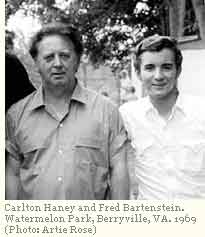

This Labor Day festival, organized by Carlton Haney, moved in 1967 to Berryville, Va. That year, Carlton Haney let Fred sleep in the medical tent behind the stage. The second night Haney was called away for personal reasons, and Fred – again in the right place at the right time – found himself being awakened by Dick Freeland of Rebel Records, asking Fred to help emcee the show that day. When Haney returned, he discovered that the shows were running on time, largely due to the energy brought to the task by the 16-year-old Bartenstein, and offered Fred a seasonal position helping with the festivals.

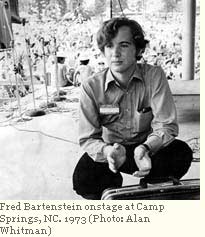

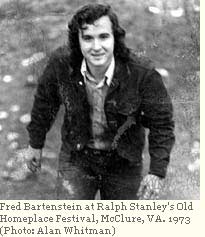

In 1969, the festival again moved, to Camp Springs, N.C. From 1969 to 1974, each summer Fred would live at Camp Springs, running various festivals and country music shows for Haney, as well as for Mac Wiseman, the Country Gentlemen, and Jim Clark’s “Peace, Love, Blues and Bluegrass” festivals. He served as the program director, emceeing throughout the weekend, and, on occasion, running the sound as well. Even after moving to Dayton, Bartenstein would still return to run a few festivals each summer.

It was at Haney’s festival in North Carolina that Bartenstein, then a college student at Harvard, along with Kathy Kaplan, produced the festival program that soon became the bimonthly, then monthly Muleskinner News, which Fred edited throughout his college years. (One can see a picture of Fred selling the News at Jim Clark’s Culpeper Festival in Neil Rosenberg’s definitive Bluegrass: A History.)  The News offered a variety of information to the bluegrass fan, from interviews with various artists and up-and-coming stars, to valuable discussions of the historical background of bluegrass, as well as a list of future appearances and festivals. In its time, the News served a valuable role. However, after Fred left his position as Managing Editor in January of 1975, the magazine appeared less frequently, and finally ceased publication in 1976. The News offered a variety of information to the bluegrass fan, from interviews with various artists and up-and-coming stars, to valuable discussions of the historical background of bluegrass, as well as a list of future appearances and festivals. In its time, the News served a valuable role. However, after Fred left his position as Managing Editor in January of 1975, the magazine appeared less frequently, and finally ceased publication in 1976.

A Cross Between Walter Cronkite and Tammy Wynette

Bartenstein’s unique background gives him a valuable perspective on the history of bluegrass music and where bluegrass might be headed. Those of his generation help connect the older and younger eras of bluegrass – they’ve gotten to see Bill Monroe at his peak, while also having had the chance to see contemporary talent emerge from the enormous shadow Monroe cast. Born in Virginia, where he spent the summers of his childhood, Fred also has lived in New York, Boston, and other big urban centers. Harvard-educated, he is keenly aware of both the history and the sources of country music. Older and younger, southern and northern, college and grassroots, to Fred, “it’s the music itself that always remains important. No matter what tensions, or even conflicts, one might see between all of these parts of my life, it has always been the music that has served as the bridge between them.” Raised in a family that stressed education and ambition, Fred was drawn to bluegrass and its emotional content. He concedes that his co-workers in the Dayton Police Department may have been right when they told him he was “a cross between Walter Cronkite and Tammy Wynette.”

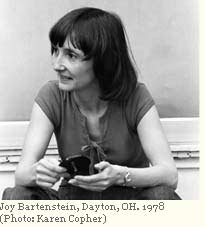

But, as Fred notes, he couldn’t have survived without that high lonesome sound, and it appears that the phase his family keeps waiting for him to go through isn’t passing anytime soon. “When I can’t walk, I’ll be listening to those same records, the classic core country stuff – Monroe, George Jones, Loretta Lynn, Porter Wagoner.” Along the way, Fred has been helped enormously by his wife Joy. “We attend concerts together, and listen to the music together. She’s my best critic, and helps me program cuts for my radio shows.” Fred and Joy (they have two daughters – neither, Fred admits bitten by the bluegrass bug) live in Yellow Springs, Ohio, home of Antioch College, where the Osborne Brothers performed at the first bluegrass college concert in 1960.

How does Bartenstein identify the music that counts, that resonates and survives? “I don’t think there is any need to go into the controversy around the question of what bluegrass is. I ask myself: Does it make a difference to the soul? I don’t build strong walls, but I do think you have to pay attention to the source of the power that is there.” The recent music Fred has been listening to gives him a great feeling of optimism. “My soul is beginning again to be satisfied.”

Fred admires those who resisted what he calls “the dry spell of the 1980s” – the Johnson Mountain Boys, Del McCoury, Hot Rize, the Nashville Bluegrass Band – and played music that was “consistently listenable.” He is even more enthusiastic about the music that has emerged since the passing of Bill Monroe. “There is a new revitalization going on in bluegrass. The death of Bill Monroe released energy and passion that, like an exploding star, freed up those fires that are now burning so brightly.” Bartenstein points to Ricky Skaggs’ “Bluegrass Rules!” as a prime example. “It’s like the National Bureau of Standards. He performs and interprets the canon, but doesn’t add much and doesn’t take anything away. It is the kind of recording that will enter into a bluegrass fan’s permanent collection and stand the test of time.” Fred admires those who resisted what he calls “the dry spell of the 1980s” – the Johnson Mountain Boys, Del McCoury, Hot Rize, the Nashville Bluegrass Band – and played music that was “consistently listenable.” He is even more enthusiastic about the music that has emerged since the passing of Bill Monroe. “There is a new revitalization going on in bluegrass. The death of Bill Monroe released energy and passion that, like an exploding star, freed up those fires that are now burning so brightly.” Bartenstein points to Ricky Skaggs’ “Bluegrass Rules!” as a prime example. “It’s like the National Bureau of Standards. He performs and interprets the canon, but doesn’t add much and doesn’t take anything away. It is the kind of recording that will enter into a bluegrass fan’s permanent collection and stand the test of time.”

“I’ve been accused of being obsessed with the music.” Fred notes. “But bluegrass is like a religion. You may have to give up a little, or sacrifice enormously, to live in that religion, to live for bluegrass. Bill Monroe had a sound he had to make, which explains the singular passion that held him in its grip. You don’t play the music primarily for fame, or to make money. It is simply because it is the music you have to make.” In reflecting on his 40+ years listening to , playing, organizing, and writing about country music and bluegrass, Fred observes, “Some part of me is a bluegrass true believer. I’m like a plant that hasn’t had sufficient soil for 25 years. But I’m optimistic that I’m getting it now, and my soul is starting to be nurtured and renewed again.”

Kurt Mosser teaches philosophy at the University of Dayton. He attempts to play both guitar and banjo with varying degrees of success.

|